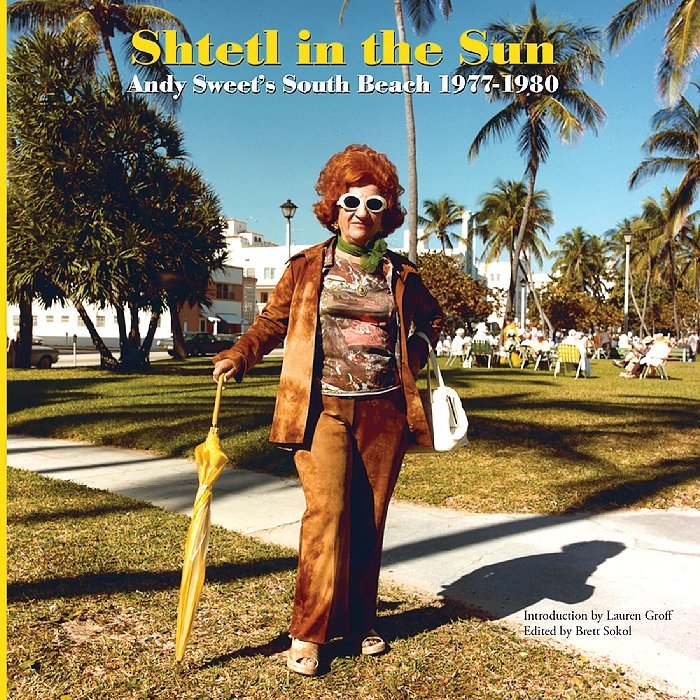

The Jewish Museum of Florida-FIU, part of Florida International University, presents the national museum debut of Shtetl in the Sun: Andy Sweet’s South Beach 1977-1980. The new museum exhibition celebrates the legendary photographer’s work in the late 1970s capturing the colorful elderly Jewish community in South Beach, before his death at a young age.

Taking a cue from the new book from Letter16 Press, edited by Brett Sokol, this is the first time a museum presents a solo show of Sweet’s work, now on view until June 23. The exhibition’s debut also coincides with the successful national release of The Last Resort, the new film directed by Dennis Scholl & Kareem Tabsch that also celebrates Andy Sweet’s work.

The landmark museum is located at 301 Washington Avenue in the heart of South Beach’s historic Art Deco District, which was ground zero for Andy Sweet (1953-1982).

Sweet’s work was almost lost forever, and was rescued thanks to the work of his sister, Ellen Sweet Moss, and her husband Stan Hughes. The exhibition will feature an intimate look inside the artist’s working process, with more than 60 images, plus original photographs that have never been shown, handpicked by Sweet’s family exclusively for this museum show.

The family is also providing a treasure trove of archival materials, shown for the first time, including some of Sweet’s original Hasselblad cameras, photo contact sheets hand-noted by Sweet, and more. The museum’s programming of events surrounding this exhibition includes an evening with Ellen Sweet Moss and Brett Sokol, on April 9.

“Andy Sweet was a true Miami Beach original. He possessed a talent and creative vision that was intrinsically linked to the zeitgeist happening here at that time,” said Susan Gladstone, the museum’s Executive Director. “The Jewish Museum of Florida-FIU is thrilled to create this first-ever museum solo show about Sweet’s work, as our own South Beach history resonates in the same radius where his creative lens took flight. There was a magical quality in Andy Sweet’s photography that comes across today.”

A testament to the powerful way his images connect across generations and cultures is evident in the early interest from other museums in the U.S. and abroad, wanting to borrow this exhibition to show in their communities.

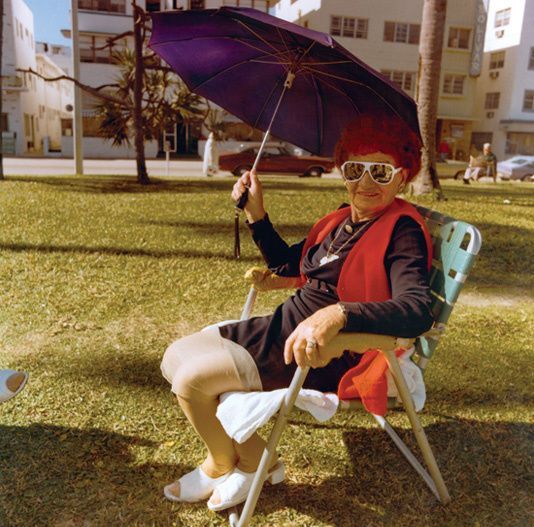

South Beach was predominantly a Jewish enclave in the late 1970s when Andy Sweet photographed the elderly population, and many of the residents were New York transplants and Holocaust survivors.

Before preservationists rescued the Art Deco buildings and designated the district onto the National Register of Historic Places, before Miami Vice transformed Miami’s image worldwide, and way before the hip and trendy renaissance of the area, South Beach was home to the largest number of Jewish retirees in America. More than 20,000 elderly Jews lived in South Beach then, within a compressed area (like a modern-day shtetl).

They banded together into a tight-knit community to help each other, often converting the lobbies of these Art Deco buildings into makeshift synagogues. Susan Gladstone, the museum’s Executive Director, was a young social worker when Sweet was documenting this community with his camera. She was assigned to work with agencies in this neighborhood, to assist the aging population.

Thirty years later, Gladstone was tapped as a historian for the film The Last Resort, the smash hit that won numerous awards in the film festival circuit and that is getting rave reviews now during its national theatrical release.

“This exhibition is about more than just nostalgia, it’s about the life of a young photographer destined to become an important artist were it not for his sudden end at the age of 28. Many of the people in Sweet’s photographs smiled back at his camera,” adds Gladstone. “Many of his subjects exuded a sense of urgency to live out their lives to the fullest on South Beach ─ some of them were still laughing, dancing, and living before it was too late.”

In the new photography book from Letter16 Press, Brett Sokol states: “Forget those jokes about South Beach in the late 1970s being the Yiddish-speaking section of God’s Waiting Room. Yes, upwards of 20,000 elderly Jews made up nearly half of the Beach’s population in those days – all crammed into an area of barely two square miles like a modern-day shtetl, the small, tightly knit Eastern European villages that defined so much of pre-World War II Jewry . . . they all still had plenty of living, laughing and loving to do. Sweet’s photos capture the community’s daily rhythms in all their beach-strolling, cafeteria-noshing, and klezmer-dancing glory.”

Also in the book, filmmaker Kelly Reichardt says: “I can’t recall exactly where I first discovered Andy Sweet’s photos but it wasn’t long after moving north . . . After you get some distance from a place, you realize there were some things you liked after all. And one of those things for me was the Miami Beach that is represented in Sweet’s photography. If only, back when I was out there on Ocean Drive, with my Pentax K-1000, if only I could have stumbled into Andy Sweet’s photographs.”

Because Andy Sweet died so young, and since his boxes of photos and negatives were lost, his work was almost lost forever. Sweet’s life was cut tragically short when he was murdered in 1982. Victim of a violent crime, he was brutally stabbed to death in his Miami Beach apartment. Citizens of Miami Beach and of Miami-Dade County were shocked and horrified by Andy’s senseless murder.

This native son, affable and fun-loving, having just entered his artistic journey and becoming well known for establishing an important visual legacy, was abruptly gone.

His family was so devastated, that for decades they could not face the emotional ordeal of what to do with his boxes of photographs. His extensive body of work exhibited a level of creative maturity far beyond his years.

Time passed, but the Sweet family and their friends kept an emotional vigil. Andy’s photographs, in boxes containing thousands of colorful prints and original negatives, became their focal point. His extensive archive would represent his richly-lived short life.

However, if there was any glory in their undertakings, there would be much more anguish — the family was heartbroken when in 2003 they were shocked to learn that a storage facility lost all of these boxes, and they feared his legacy was forever lost.

Then, suddenly a stroke of good luck would change their lives! In 2006, Andy’s sister, Ellen Sweet Moss, and her husband Stan Hughes, miraculously discovered boxes of precious test-prints, contact sheets and work prints that no one knew existed. The couple then decided to dedicate the greater part of their lives to maintaining the memory of Sweet’s work.

Because these newly discovered boxes contained no color negatives, and because the test-prints in these previously undiscovered boxes were faded after so many years, the project would require extensive restoration.

Hughes decided to research into Sweet’s early work and his style of photography, to be able to try to restore them to their original colors with the guidance of Gary Monroe (Andy’s best friend and photographic partner during their South Beach days).

For years, Hughes spent over 12 hours a day painstakingly and tirelessly restoring these new-found test-prints to their original colorful glory, using new advances in digital photography. They made it their life mission to ensure that Sweet’s work reaches as many people as possible with the Andy Sweet Photo Legacy.

The family’s mission is now at a turning point, with the spectacular success of the film The Last Resort by Dennis Scholl and Kareem Tabsch, the book by Brett Sokol, and the museum exhibition by the Jewish Museum of Florida-FIU. All three current manifestations of Sweet’s work are taking his creative vision to audiences worldwide.

More about the artist . . .

When he returned home to Miami Beach after receiving a Master’s degree in Fine Arts from the University of Colorado at Boulder in 1977, Andy Sweet was on a mission with his friend Gary Monroe to photograph the Old-World Jewish culture that then distinguished South Beach.

While in graduate school, Andy was part of a small faction of young artist-photographers who were discovering the creative possibilities of color imagery. His beach-ball hues perfectly described the vivid light and lively culture he explored and portrayed, a culture that many others found bleak and pedestrian.

Andy’s aesthetic was as fresh as his colors. He rejected formalist theory and idea-driven imagery in favor of immediate and unmediated responses, of living it up and aligning himself with the people he knew he was privileged to photograph.

Andy admired the work of Diane Arbus, and like her he rejected the notion of self-conscious art making. The pure and spirited photograph was what mattered. He knew he was an artist but his aesthetic, his intellect, and his ego required that he conceal this fact in service of achieving the caliber of photograph he desired.

Intuitive, but certain, each click of his camera’s shutter release was an affirmation. He joyously photographed in this way until his death in 1982. He was only 28 years old.